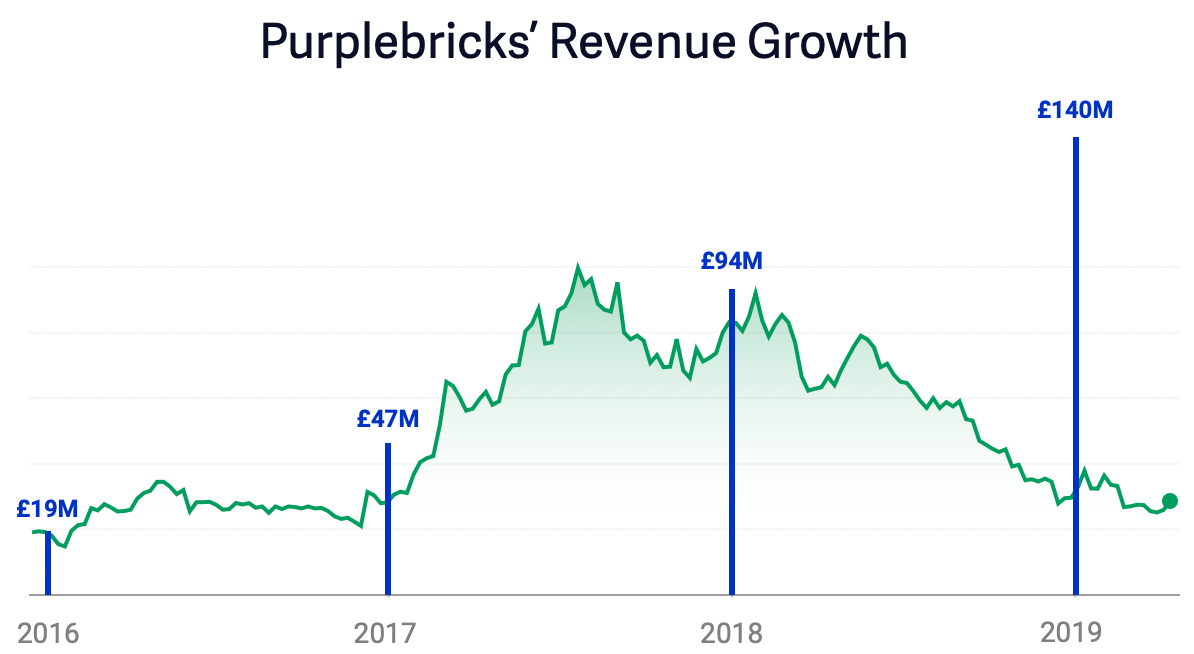

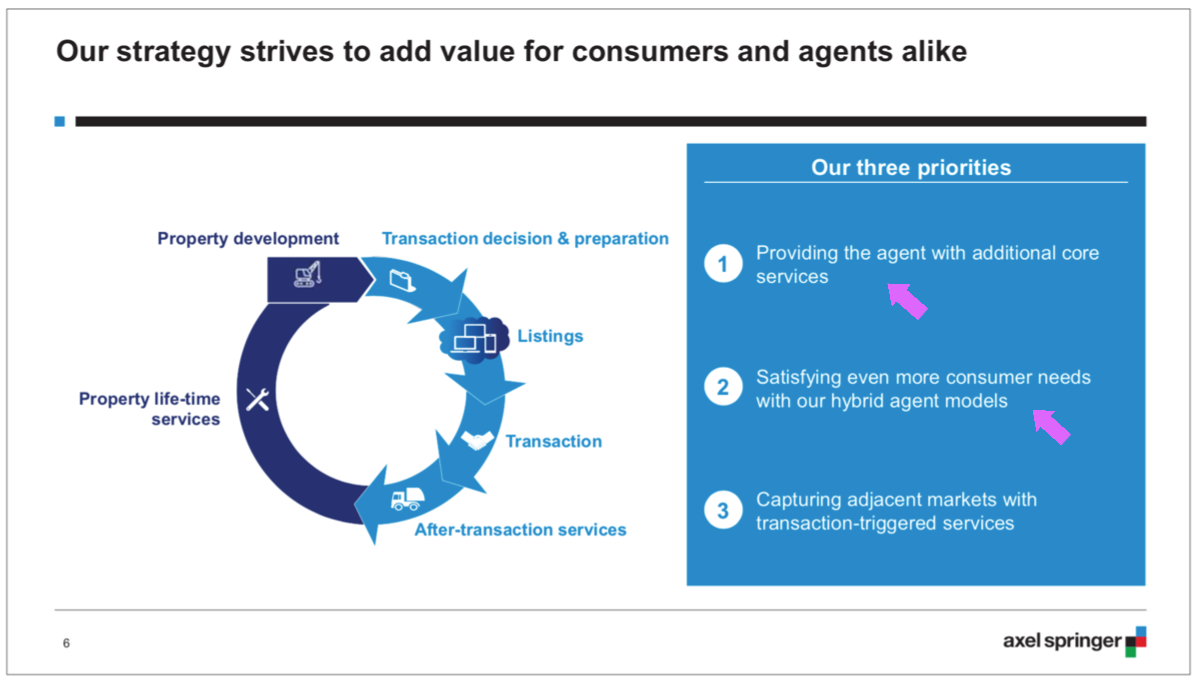

Because of their novel operating models, Redfin and Purplebricks have a great deal of direct control over their agents, allowing them to standardize processes to deliver a more uniform and efficient consumer experience.

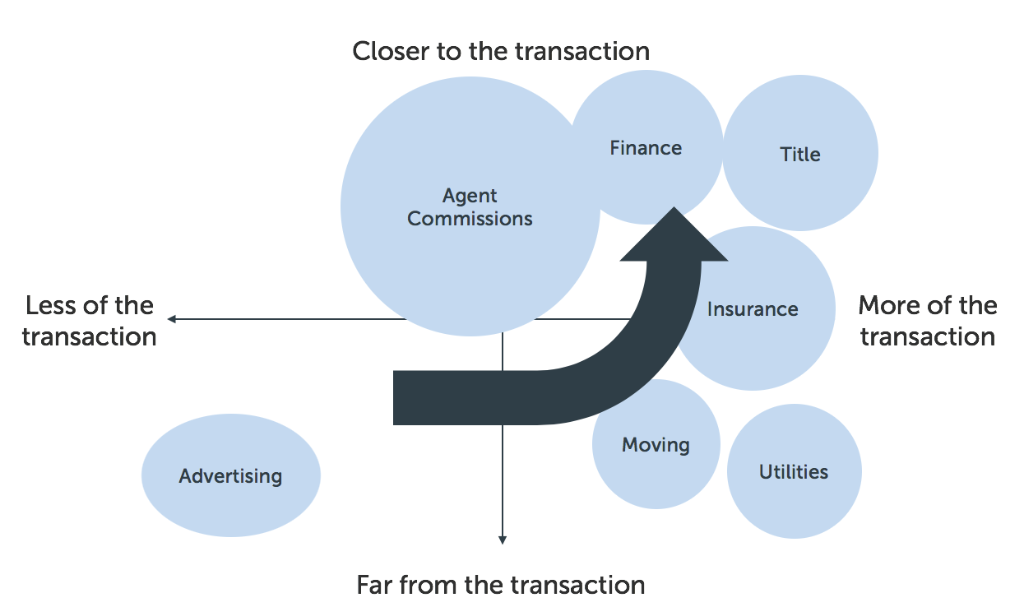

For Compass to break out of the traditional brokerage mold and fully realize its ambitions, it needs to become more than a brokerage, and more than a technology company. It needs to become a platform. And in doing so, radically change brokerage economics and, consequentially, the role of agents.

The platform play

To become a true real estate platform, Compass first needs to become a consumer destination.

Redfin has its portal, Uber has its app, and Purplebricks (in the U.K.) has its web site. In each case, consumers go directly to the company — not an agent or driver — to start their journey, giving the platform owner unprecedented ecosystem power. The platform owner controls the lead, distributes it, and takes a healthy cut of the revenue. If an employee or contractor doesn’t perform to expectations, the company removes them. The platform owner is in complete control.

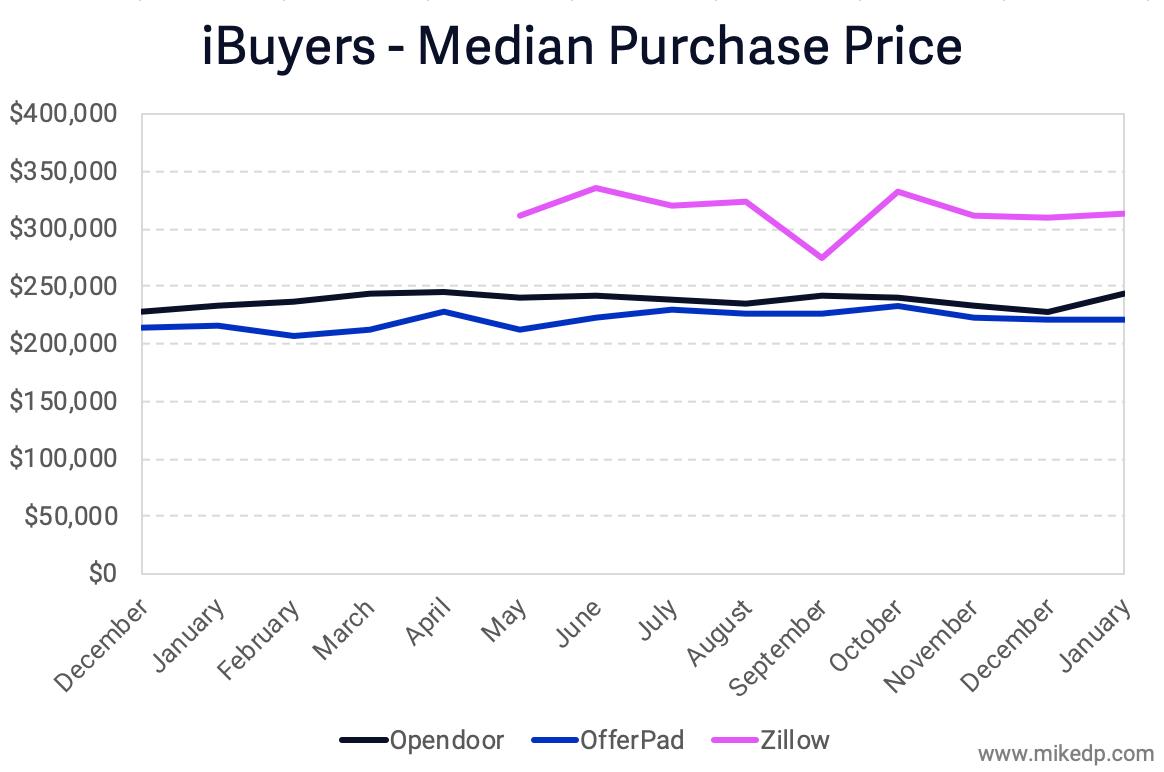

For Compass to become a consumer destination, it needs eyeballs. The most effective strategy — and likely the only possible strategy given the market dominance of Zillow — is to build consumer traffic with the draw of exclusive listings. It’s a similar strategy to Netflix and Amazon’s exclusive video content. If the Compass web portal advertises houses for sale that aren’t available anywhere else, it draws consumers to the platform.

Building exclusive content

The secret to building audience with exclusive content is scale: Compass needs significant market share for this strategy to work. Pocket listings, which are withheld from the MLS for a period of time, have been around for years, but never employed at this scale. Compass needs to advertise so much exclusive content, including coming soon listings, that consumers can’t afford to miss it.

The evidence that Compass is strongly promoting exclusive content is plainly visible on its web site. In fact, exclusive content is the primary call-to-action on Compass’ web site, starting with top billing on its site navigation.