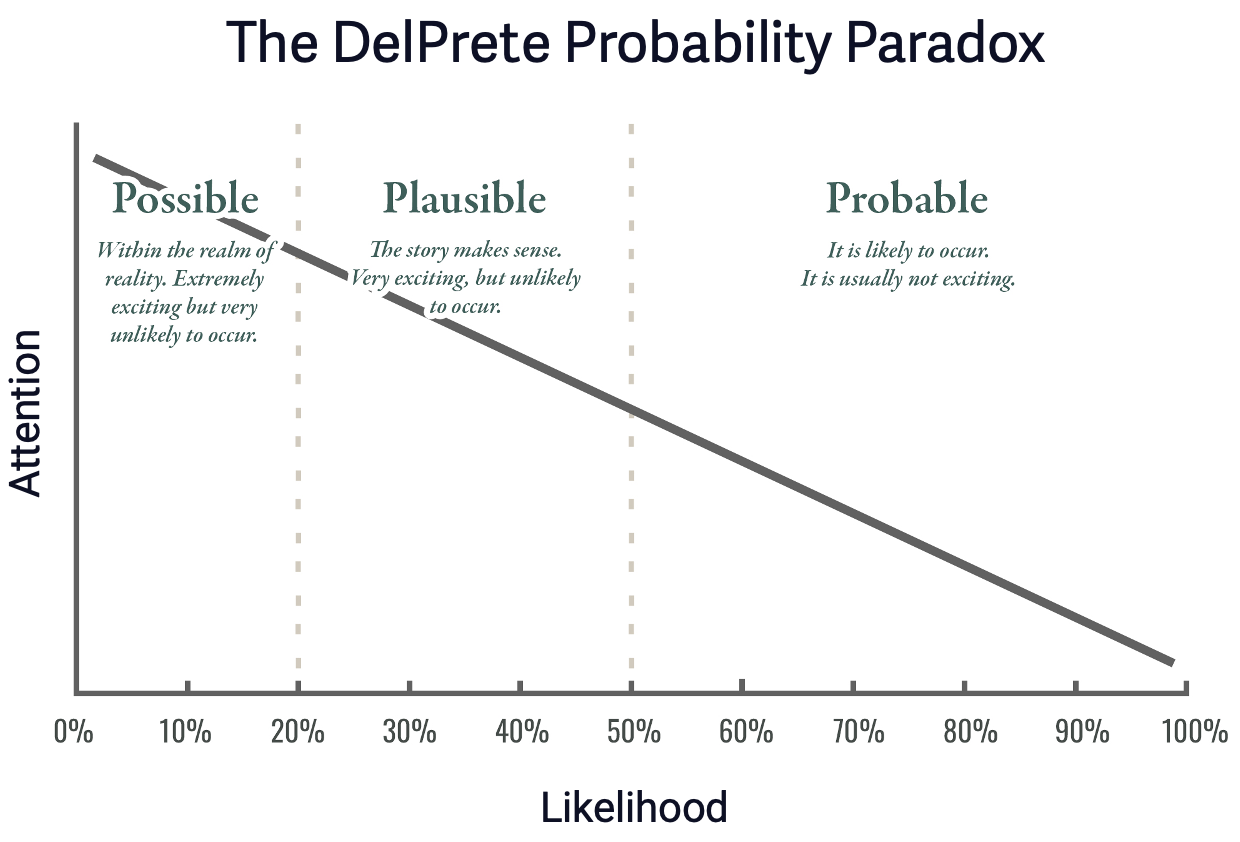

The DelPrete Probability Paradox

/There is an inverse correlation between how likely something is to occur and how much attention it gets – a phenomenon a friend has dubbed the DelPrete Probability Paradox.

Why it matters: This leads to attention being focused on the highly exciting, yet least likely scenarios, which dilutes focus and clarity while creating noise and distraction.

Getting informed and being entertained are two separate things; boring headlines don’t sell papers.

Real estate is rife with possibility – news headlines and conference agendas are packed with topics that exist in the realm of the possible and plausible, but not necessarily probable.

Will AI replace agents? What will happen to interest rates? How will the commission lawsuits change the industry?

The reality is that no one knows, and the most probable outcomes are slow, incremental deviations from the current state, not radical changes.

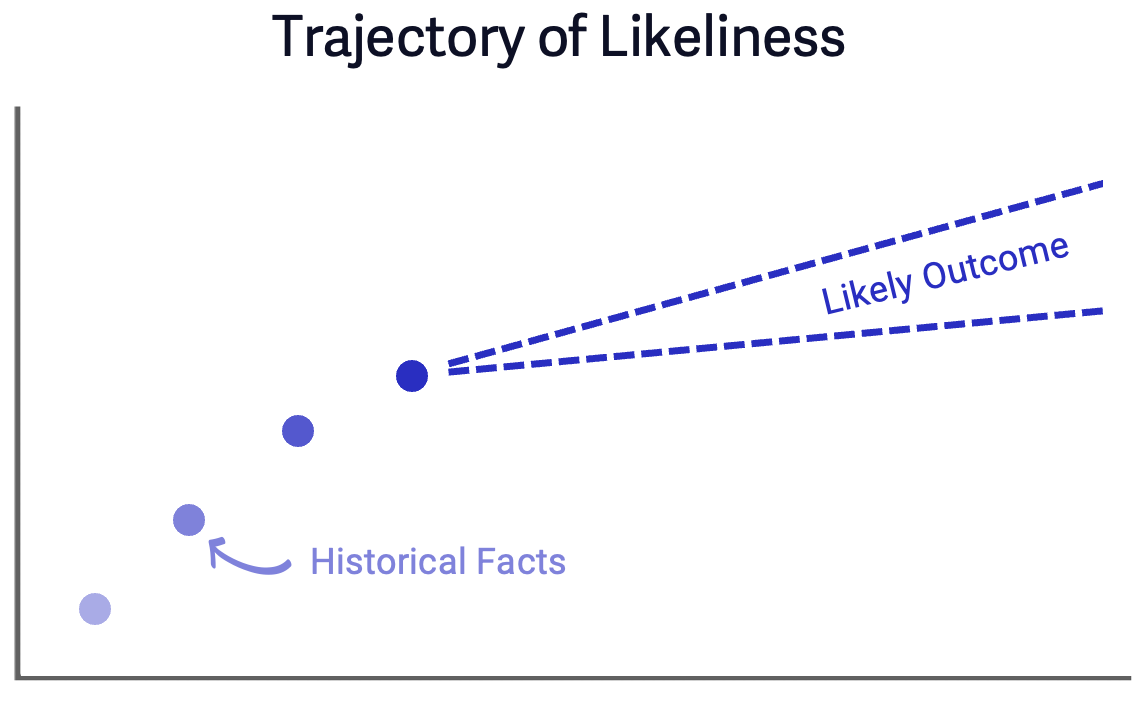

Probability revolves around the existence of data, facts, and evidence – the more we know, the more certain the predictions.

The least likely events – the possible – generally exist in a reality light on facts and flush with speculation.

Facts are important; they form a trajectory of likeliness – plotting them over time and triangulating data points can identify likely outcomes.

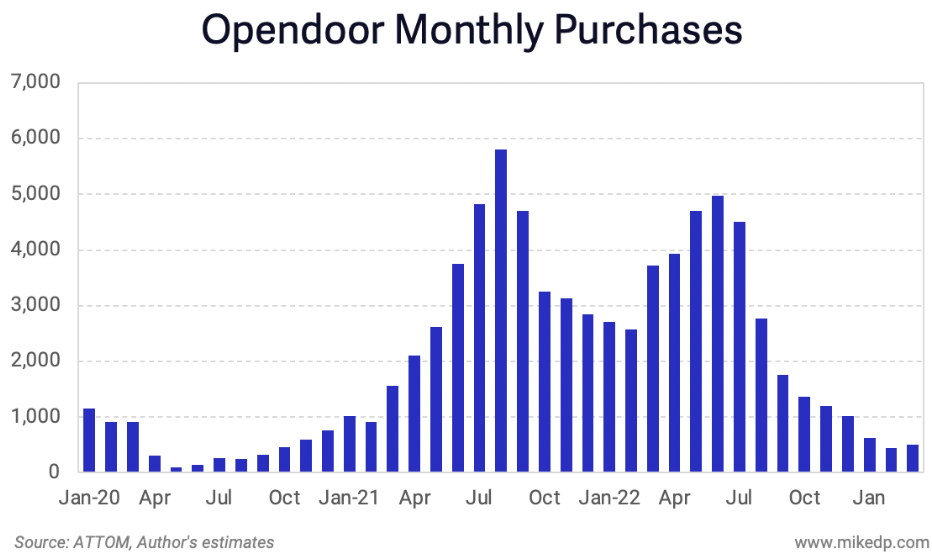

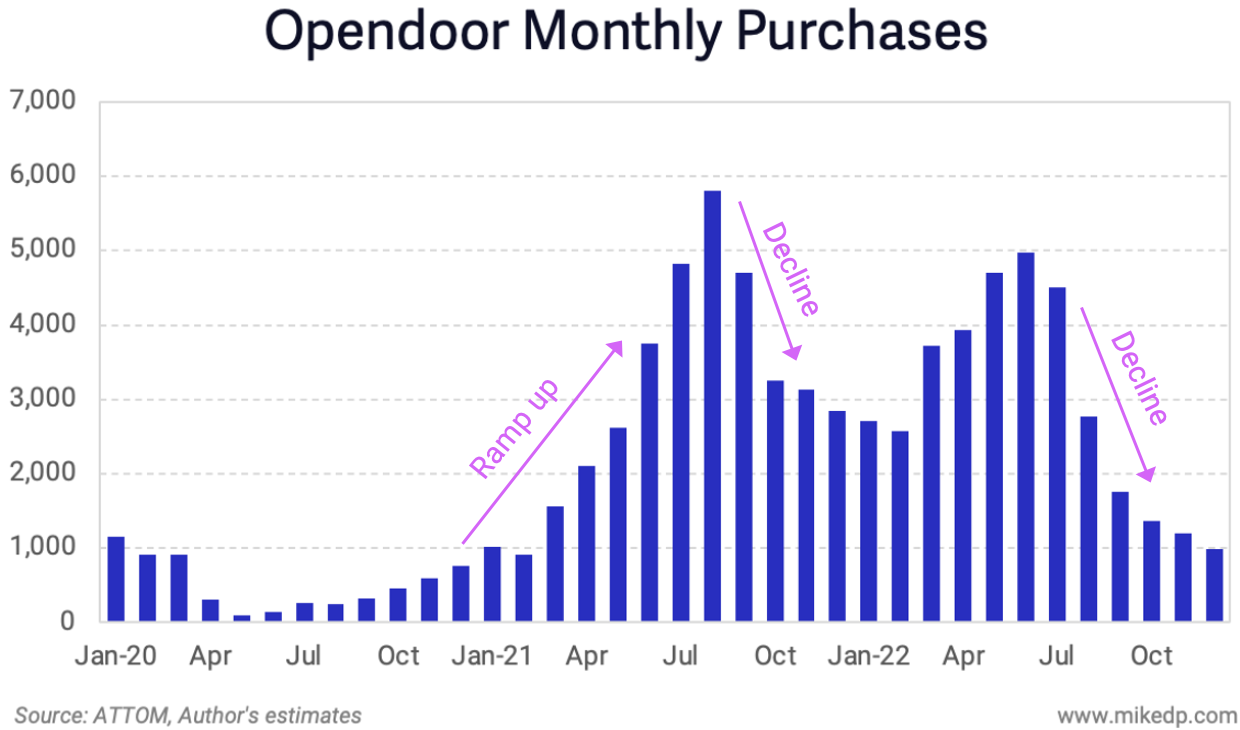

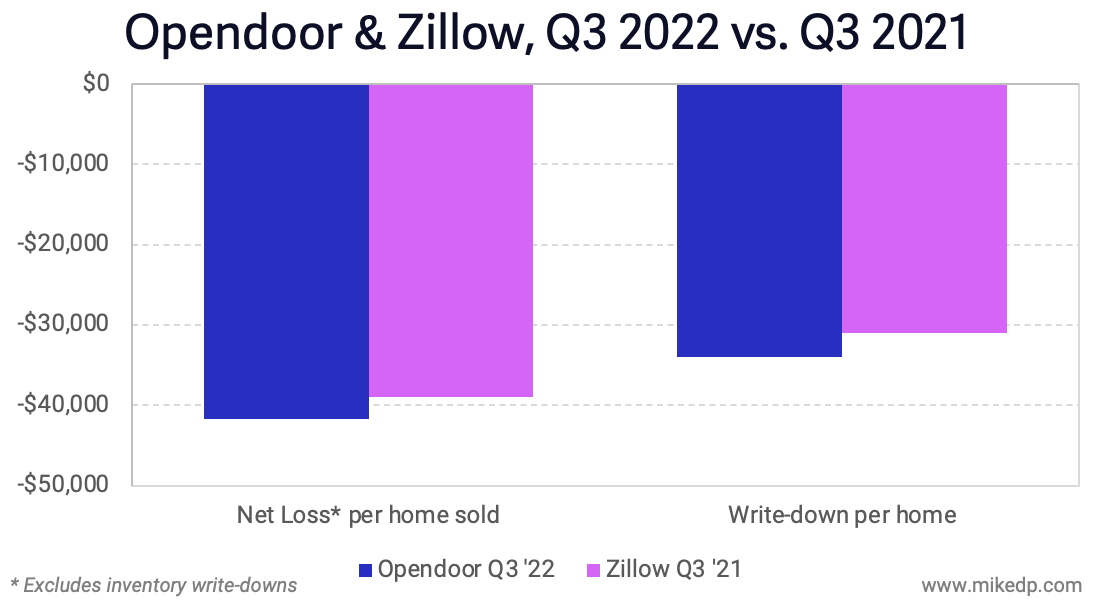

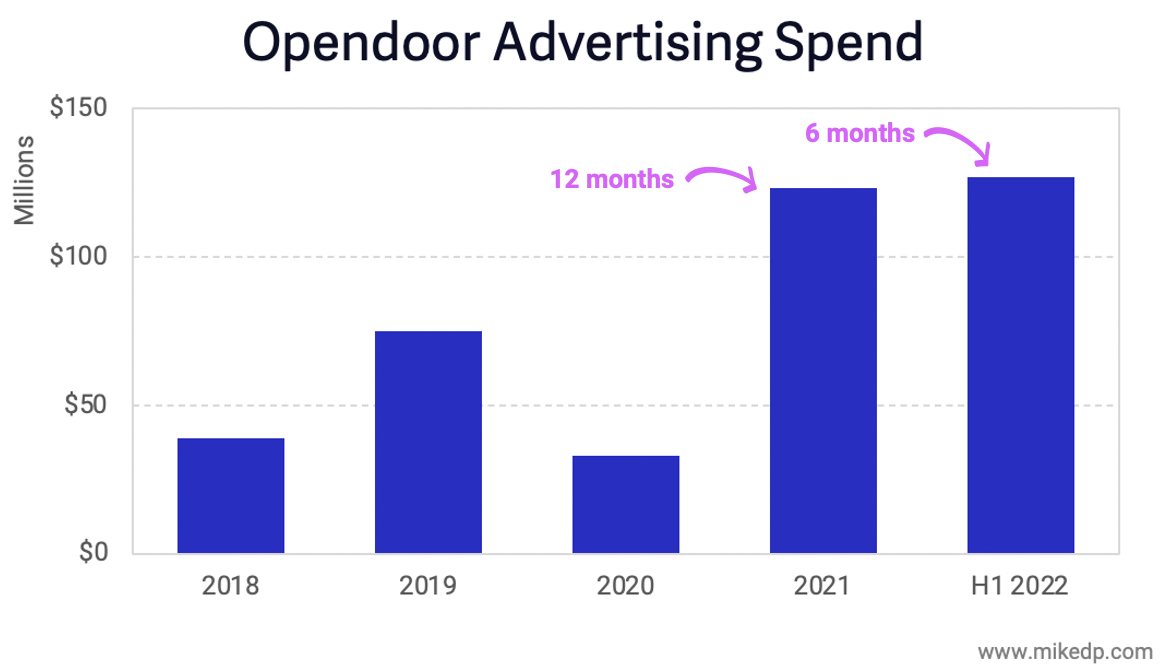

For example: Opendoor’s IPO prospectus presented a very plausible argument supporting its ability to attach adjacent services to a real estate transaction.

The company asserted that because it had success attaching title & escrow services to its sales, it would be able to attach other adjacent services like home loans.

The story made sense – to those outside of the industry – but in the end it didn’t work and Opendoor shut down Home Loans. Plausible, yes, but not probable.

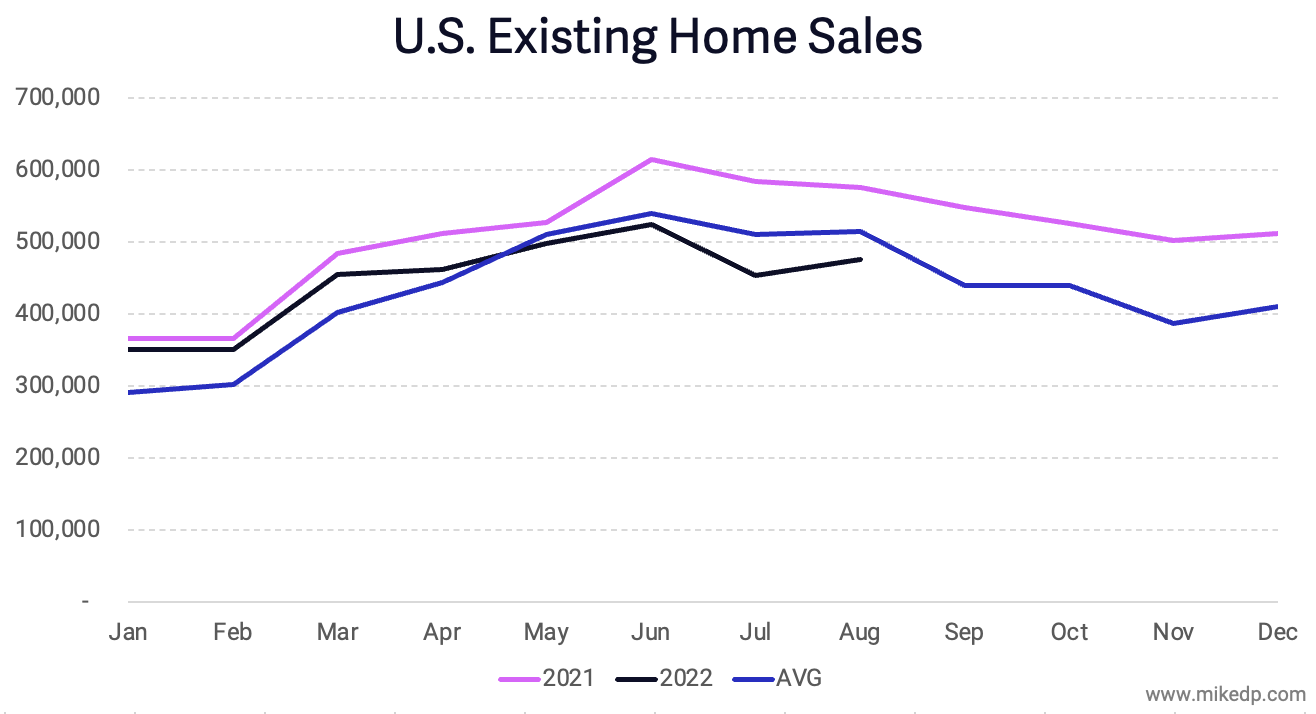

Inertia rules: Newton’s First Law states that an object in motion will stay in motion unless acted upon by an outside force – in other words, systems tend to remain constant.

Consider the percentage of homeowners that use a real estate agent to sell their home: even after the introduction of Zillow, Opendoor, and billions of dollars in venture capital pushing alternative models, it remains at a 40 year high.

Speculation is running high with the recent NAR settlement; my thoughts were summed up in this Bloomberg article.

"Right now, everyone is turning this ruling into what they want it to be,” said Mike DelPrete, who teaches courses on real estate technology at the University of Colorado Boulder.

“Some people are saying not much is going to change. Others want the story to be that it’s a seismic shift for the industry. The whole thing is being driven by fear and uncertainty.”

The bottom line: Don’t confuse news with entertainment – news is meant to inform, entertainment is meant to distract.

Making smart decisions requires cutting through the noise and gathering evidence, pattern matching, and distilling insights.

But it's easy to get distracted, which is the crux of the DelPrete Probability Paradox: the less likely something is to occur, the more attention it gets.