Zillow, Power Buyers, and the Challenge of Attaching Mortgage

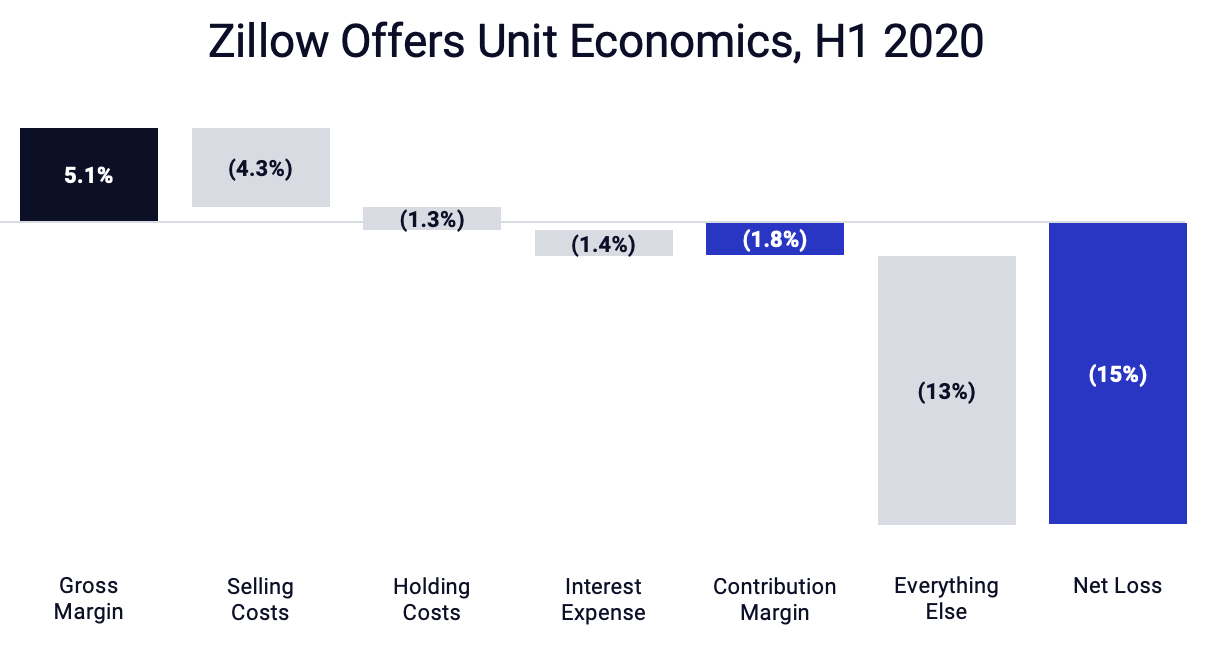

/In 2018, Zillow set itself lofty goals when it entered the mortgage business. Three years later, Zillow's actual performance is far, far below its predictions, highlighting how difficult the mortgage space is, not just for Zillow, but for every real estate tech company targeting mortgage as a lever for growth.

Setting High Expectations

Zillow's 2018 Annual Report, released after Mr. Barton assumed the CEO role, clearly set out the company's 3–5 year goals in mortgage:

Mortgages Segment

Zillow Home Loans achieves a 33 percent attach rate to Zillow Offers, up from zero in 2018.

Zillow Home Loans originates more than 3,000 loans per month, up from nearly 4,000 MLOA loan originations in all of 2018.

The 33 percent attach rate to Zillow Offers is down from the lofty 75 percent attach rate quoted earlier by Mr. Rascoff in Zillow's 2018 second quarter earnings call:

"So for anybody who is wondering why we just bought a mortgage lender, just to hit some of those numbers again, at a mere 10,000 homes sold a month from Zillow Offers, a 75% attach rate gets to over $800 million a year of revenue opportunity for mortgage origination.”

Three years and over 10,000 homes bought and sold later, the reality is a mortgage attach rate to Zillow Offers of less than 1 percent.

(Zillow and Opendoor's attach rate is based on the markets where the service is live.)

Zillow's goal of originating 3,000 loans per month, or 36,000 in a year, remains highly aspirational. Loan originations actually took a step backwards in 2019 before rebounding in 2020 due to the pandemic and record low interest rates -- but are still less than 20 percent of Zillow's original goal.

It's worth noting that proportionally, Zillow's purchase volume (versus refinance) has steadily declined from 97 percent in 2018 to 31 percent in 2020 (and down to 10 percent in Q1 2021). The growth in Zillow Home Loans is being fueled by refi.

The Rise of Power Buyers

Ironically, Zillow is attaching more mortgages to Opendoor-owned homes than it is to Zillow-owned homes. Just let that sink in.

This bizarre fact underscores how difficult it is to attach mortgage to an iBuyer home for sale; most prospective buyers are already pre-approved. It's too late in the buyer journey to introduce and attach a new financing option.

Which is why the smart money is on companies -- I call them Power Buyers -- focused exclusively on attracting buyers earlier in the process with products like cash offer and buy before you sell. Examples include Homeward, Orchard, and Knock, and initiatives like Opendoor's Cash Offer and Zillow's video tease of it helping a Zillow Offers seller secure financing for their next purchase.

There are a multitude of companies attempting to sell mortgage and other adjacent services to their customers in an effort to increase profits. For the time being, the Power Buyers are in the lead with mortgage attach rates approaching 80%, with the iBuyers pivoting their models to catch up. Zillow's experience shows that it's a long, slow road, requiring big investment, patience, and a smart, consumer-first approach.