CAC-attack: The Cost of iBuyer Customer Acquisition

/Over the past three years, the largest iBuyers -- Opendoor, Zillow, and Offerpad -- have spent over $200 million advertising directly to consumers. That spend peaked in 2019 before slowing during the pandemic. Historically and today, Opendoor appears to be vastly outspending its competition -- a reflection of its size, scale, and ambition.

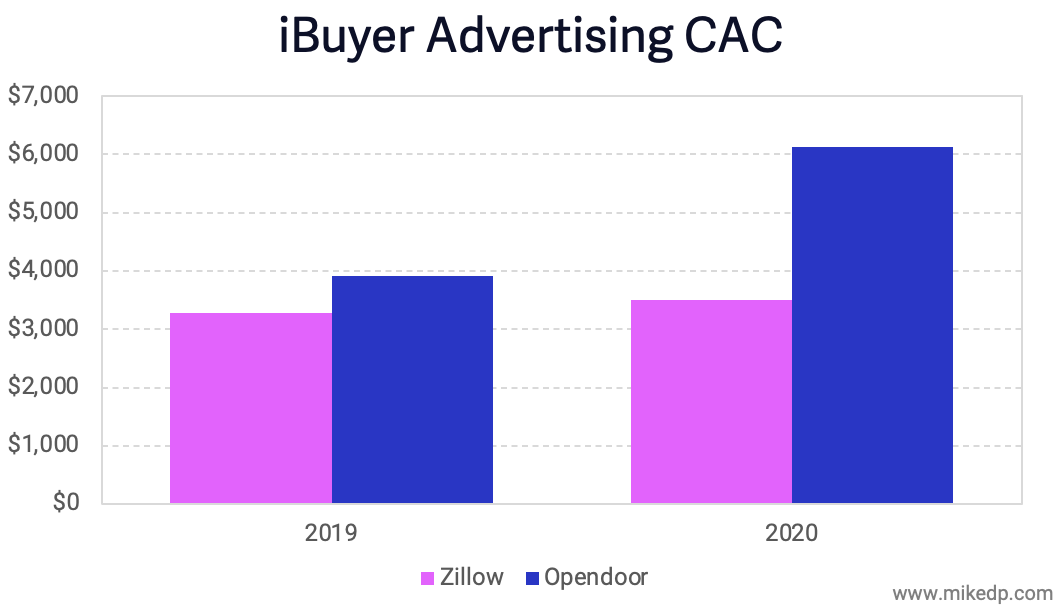

Historically, Opendoor has bought and sold more houses than its iBuyer peers, so it's important to consider the advertising expense per customer, or customer acquisition cost (CAC). Last year appears to be an expensive outlier for Opendoor.

Generally, it's what you would expect: between $3k–$4k in a normal year. Given that each iBuyer pays a 1 percent referral fee to agents for a closed lead (or $2,500 on a $250k home), the numbers make sense. It's also a blended average, so mature markets are likely less expensive while new markets are more expensive.

A broad comparison, which includes newly-released data from Offerpad (with a CAC of about $3k), and advertising expenses from Redfin's brokerage business, provides further context around the iBuyer spend.

Some interesting observations:

Customer acquisition costs for the majors iBuyers is all roughly the same: between $3k–$4k (if we consider 2020 an outlier for Opendoor).

Zillow, with its massive audience advantage, has to spend much less on advertising, and has a meaningful CAC advantage.

Compared to Redfin's brokerage service (which also has the advantage of an existing portal with millions of visitors), the iBuyers are spending 2x–4x more to acquire each customer. This is not an exact corollary, but is reflective of how difficult it is to convince consumers to try something new.

Shifting Headcount

The Sales & Marketing line for each iBuyer includes headcount expenses for employees involved in the sale of homes, a fairly broad definition. And there was a noteworthy shift in headcount during 2020.

Opendoor laid off staff and saw a "decrease of $26.7 million due to headcount reductions," while Zillow saw an "increase of $21.8 million in headcount-related expenses." Opendoor was trimming its sails while Zillow continued to invest for a future recovery; the advantage of being well-capitalized during 2020.

A Note on Methodology

Customer acquisition cost is calculated based on the total advertising spend divided by the number of homes purchased in a period of time. Direct advertising and headcount expenses are taken from each company's public filings, which is straightforward if you know where to look and are willing to do a lot of math.