International And U.S. Markets See 50-75% Drop In New Listing Volumes

/As the pandemic and associated effect on the real estate market spreads, one of the best leading indicators of a decline in transaction volumes -- new listings -- has dropped an average of 63 percent in the earliest hit markets. Seattle, the Bay Area, and New York City -- along with Italy and the U.K. -- were among the first markets hit, and are the best examples of what comes with strict lockdowns.

Declining Market Activity

In Seattle (King County), the number of new listings is down 54 percent on a weekly basis, and continues to trend lower.

On a weekly basis, new listings in the East Bay market of California are down 70 percent since the start of shelter in place orders. Listings typically increase at this time of year.

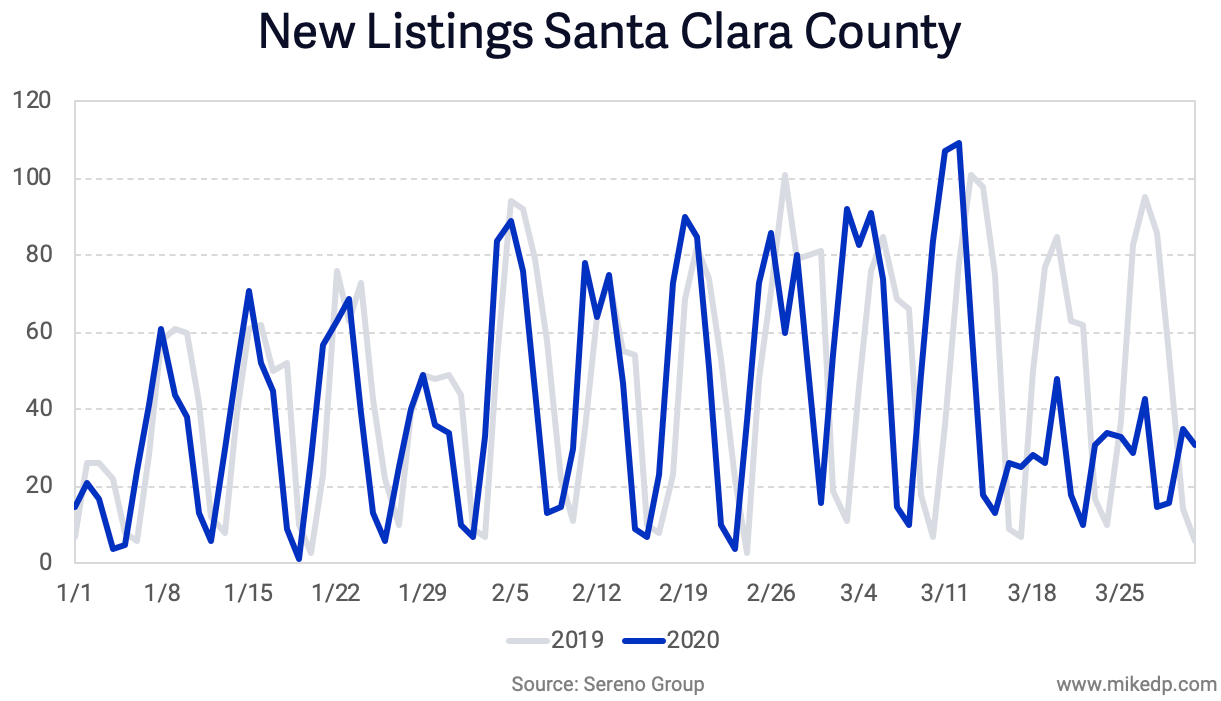

In Santa Clara county, which went on lockdown March 16th, new listings are down 48 percent on a weekly basis.

In New York City, new listings are down a whopping 78 percent across Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens, and continue to trend lower.

Many shelter in place orders took effect in mid-March, so we’re just starting to see the effect on the housing market.

International Peers

The trend is similar in a number of international markets. According to Zoopla, the #2 portal in the U.K. (which exclusively shared the following information with me), new listing volumes are down 70+ percent across the country. It’s a shocking decline that will have ramifications across the industry for the rest of the year.

In Italy, a top portal shared with me that new listings were down 60 percent from normal volumes during the third and fourth week of lockdown.

It's important to note that this appears to be the bottom; after 2-3 weeks of lockdown, new listings were down 60 percent and have not dropped any lower.

A drop in new listings directly correlates to the severity of lockdown. Some international markets, like Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden -- with less stringent lockdowns -- have not seen a dramatic drop in new listing activity.

The Ability vs. The Will To Buy A Home

When evaluating the pandemic’s effect on the market, it’s tempting to focus on the legal, logistical, and practical aspects of transacting real estate: is it an “essential” business, can open homes take place safely, and can closings occur online?

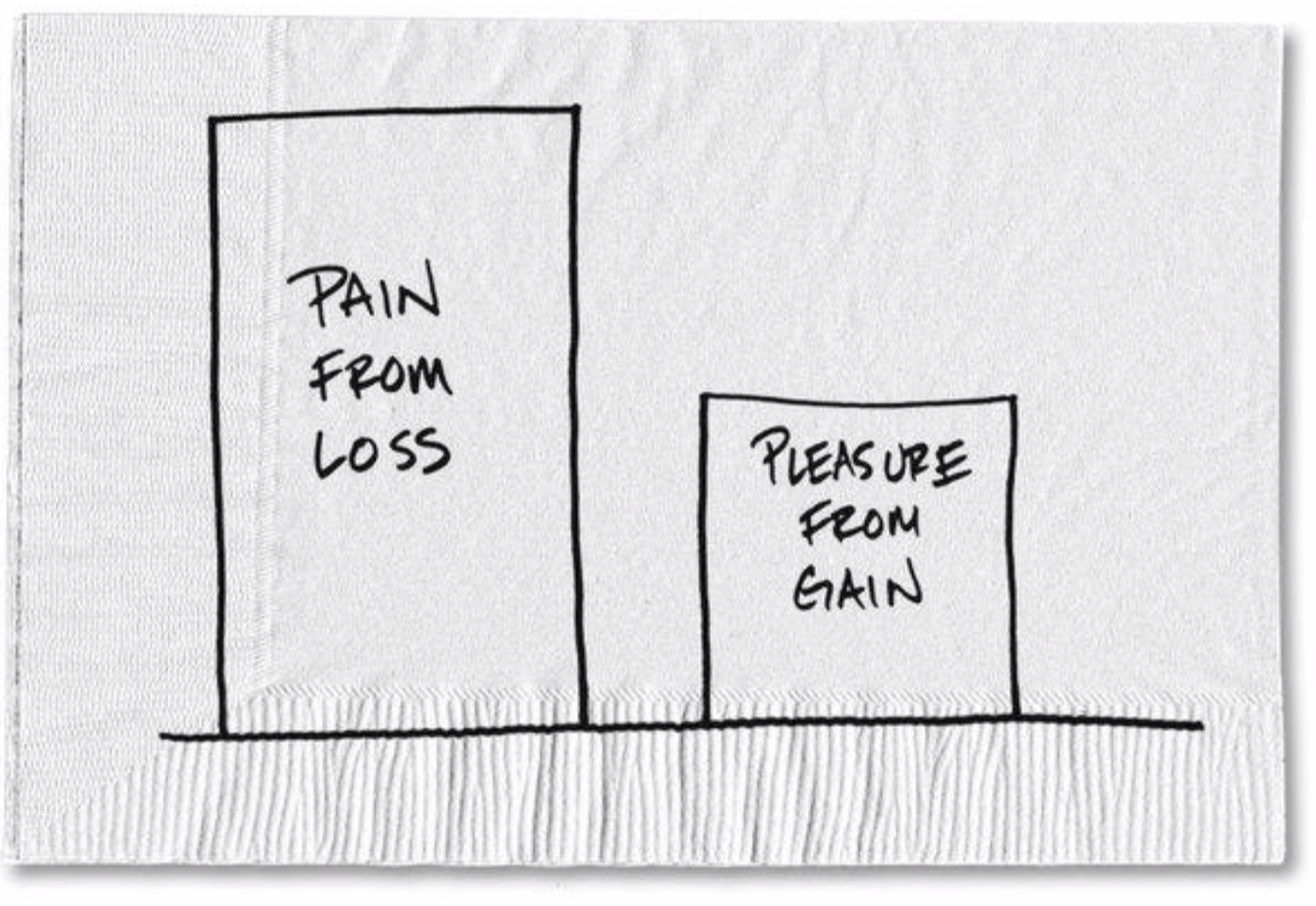

But that analysis misses an important psychological piece: Will consumers buy homes? Given the incredible market uncertainty, job uncertainty, and health and safety considerations, will consumers choose right now as the ideal time to buy or sell a home, or will they wait? Just because they can, doesn’t mean they will.

A Mild Case of Confirmation Bias

Many markets have yet to experience the full effect of the pandemic and lockdowns on home sales. Assuming it takes 90 days to sell a home, from listing to close, it will take several months to see the effects of a drop in new listings.

Given that inherent delay, there’s plenty of data available -- especially in markets that have yet to be hit -- that everything is fine. Homes are selling, listings are coming to market, and buyer demand remains strong.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, and favor information in a way that confirms one's prior beliefs or hypotheses. It’s quite easy for a real estate professional, who believes their market won’t be affected like the others, to find evidence to support that belief.

Evidence from international markets such as China, Italy, and South Korea, plus leading indicators from the first markets to be hit in the U.S., clearly shows the effects of strict lockdowns. The key criteria as the pandemic and lockdowns spread is timing; just because the tidal wave hasn’t hit yet doesn’t mean it won’t arrive.